Reflections on the History of the Imperial Examination System

By Isaac Tang

Contents

- Introduction

- Getting to the Imperial Academy

- The Stelae of Advanced Scholars

- The Exhibition of the Chinese Imperial Examination

- The Biyong Hall

Introduction

It should come as no surprise that the written examination, dreaded by students throughout the world, was invented in China, a country whose people are often stereotyped to display academic prowess. Known as keju, the written examination system was a sophisticated and integral part of Imperial China that determined the rise and fall of men for over a millennium. This is true even in Chinese legends and folktales, reflecting how success in the examinations elevated people to almost mythic status in the public consciousness. However, although it was birthed from idealistic minds dreaming for a truly meritocratic and harmonious society, its imperfections ultimately led to repeated struggles between academia and practicality, cultural conservatism and societal progress, culminating in the spectacular collapse of the Qing Empire in the face of modernism and industrialism.

Getting to the Imperial Academy

With this history in mind, it was with great curiosity that I conducted my visit (albeit short) to the Imperial Academy (Guozijian) in Beijing. It was a hot autumn Saturday, and the air quality was not the best, with light grey haze enveloping the city. In the late morning, I had visited the Drum Tower where from the viewing platform atop a vertiginous flight of stairs, the Everlasting Spring Pavilion of Prospect Hill could only be seen as a silhouette. Now, I had arrived at the Lama Temple subway station and walked out an exit into an isolated courtyard. In this courtyard, there was a tree and a clothesline hanging before a dark grey brick wall, producing a strange sense of serenity which I hoped would be a foretaste of the quietness that guidebooks promised would be found within the Imperial Academy. As I myself was preparing to sit important examinations at home, I also hoped that this visit would be a much-needed source of inspiration and motivation.

However, any serenity would be short-lived as I made my way towards the Imperial Academy past the Lama Temple on my left. The road was choked with tourists and visitors to the Lama Temple, where plumes of incense could be seen rising above the crimson walls and curved roofs. There was a terrible din mixed with the honking of cars and rush of motorcycles. Numerous stalls were set up along the road where a gaudy display of offerings and Buddhist paraphernalia were sold. No relief from the noise and crowds could be found even after turning into Guozijian Street, which was lined with majestic scholar trees. This underscored the indisputable recommendation never to visit popular tourist spots in China during the weekends. With some nervousness, I purchased my ticket to the Imperial Academy at the entrance of the Confucius Temple where, above the high grey compound walls, its wooden blue-and-green patterned beams peaked out beneath the royal yellow eaves and amidst the emerald leaves. It should be noted that it is not possible to buy a stand-alone ticket to the Imperial Academy; the ticket provides entrance to both the Academy and the Confucius Temple. The front gate of the Imperial Academy is strictly used as an exit.

The Stelae of Advanced Scholars

It was a relief to discover that the guidebooks were indeed honest in describing the Imperial Academy as “a haven of scholarly calm and contemplation”—even on a weekend. It seemed that for the masses, the appeal of dedicated scholarship and study could never compete with the appeal of superstition. The front courtyard of the Confucius Temple was a marked transition from chaotic noise to orderly quietness. Immediately feeling more relaxed, I proceeded to inspect the many stone stelae displayed there. The stone stelae were the main objects that I had long desired to see with my own eyes because these contained the names of all the advanced scholars (jinshi) from the Ming and Qing Dynasties (a period of over five hundred years) inscribed for all posterity to see and marvel.

However, these stelae were a great disappointment because it appeared that, over time, much of the etched calligraphy had faded, plunging the names of many scholars, who had dedicated years of their life to rigorous study and memorisation, into obscurity and possibly oblivion. Instead of affirming the illustrious grandeur of academia, this experience demonstrated the perishable nature of earthly knowledge. I felt a sense of sadness and pity for these scholars whose efforts, though like the fabled carp that swam pugnaciously upstream against the torrents, were ultimately washed away by the currents of Time into irrelevance.

At the western side of the front courtyard was a door which led to the Imperial Academy. Passing through the ‘Gate of Supreme Learning’ (Taixuemen), the grand Glazed Memorial Arch came into view as well as two beautiful pavilions housing two large stelae standing magnificently on the shells of stone tortoises. Unfortunately, I am unable to read Classical Chinese but I have no doubt these stelae were imparting some deeply meaningful message. There were a few tourists roaming about as well as a group of little children in green uniform, presumably part of a Confucian school excursion that was somehow sadly taking place on a Saturday.

The Exhibition of the Chinese Imperial Examination

The eastern building of the Imperial Academy had been turned into ‘The Exhibition of the Chinese Imperial Examination,’ which I entered with great delight. I am glad to say that it was nothing like the frankly unpleasant experience I had at the National Museum of China, where I was accosted by security guards and innumerable tourists, and where appreciation of the artefacts were seriously hampered by the crowds and the obnoxious noise level. Here, there were very few people and I could enjoy viewing the exhibits and reading the many well-written English descriptions in peace. It certainly does not go into as much depth as, say, Benjamin Elman’s A Cultural History of Civil Examinations, but it does provide an excellent introduction to the subject.

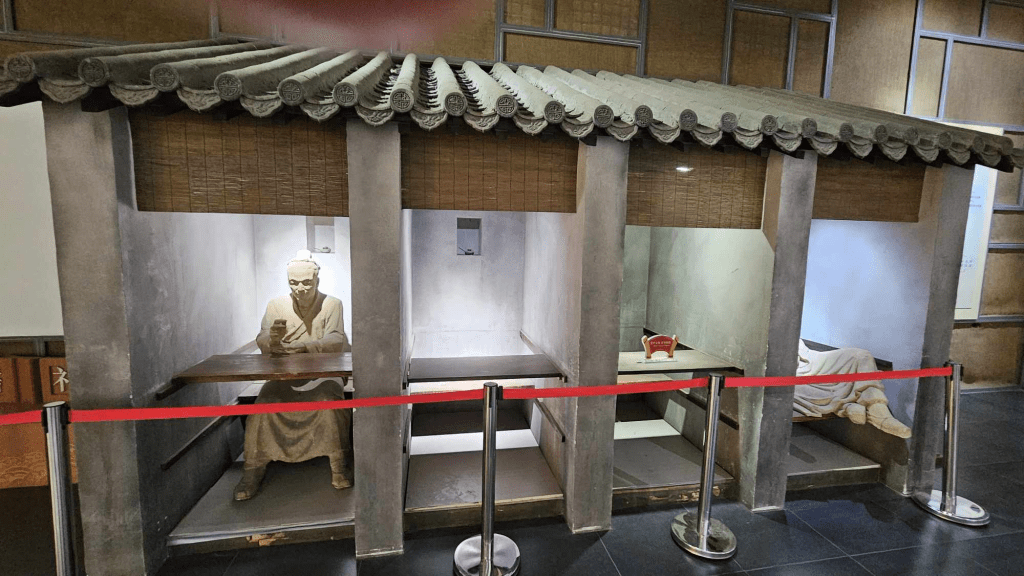

The exhibition discussed the development of the Examinations through different dynasties as well as its complex structure, mainly consisting of three important examinations—the Provincial, the Metropolitan and the Palace Examinations. Finally, it showcased the impact of the Imperial Examinations on a global stage, influencing other East Asian countries like Korea and Vietnam and also Western nations, directly leading to the modern examination system that continues to afflict youth worldwide.

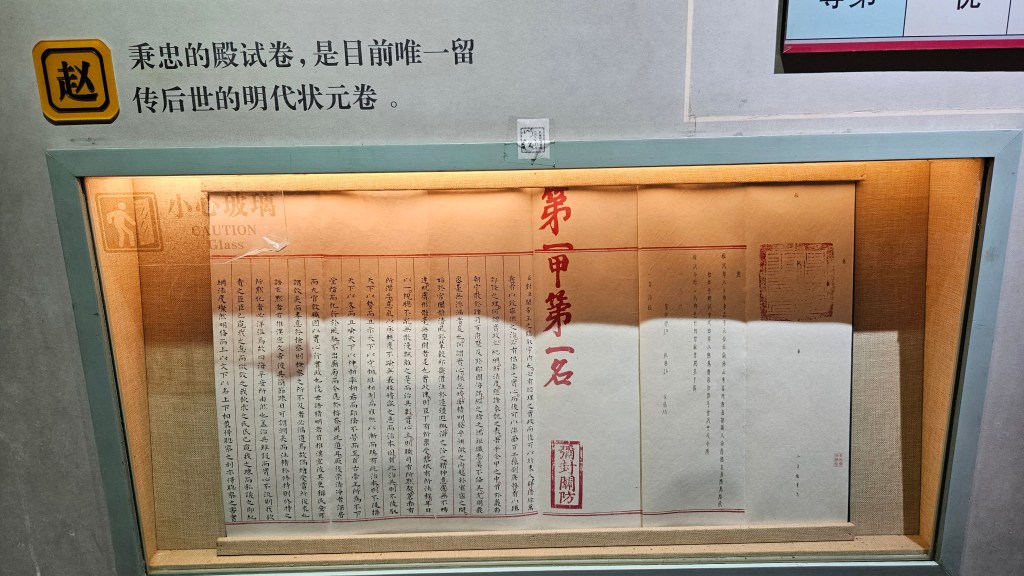

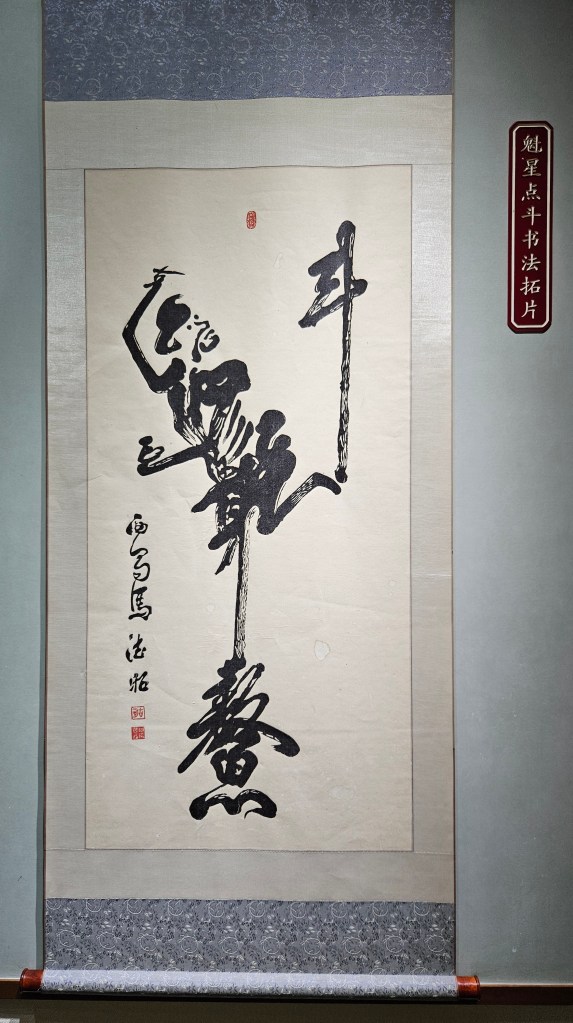

There were sample essays on display as well as some very interesting calligraphy, such as the one shown here, where the Chinese characters have been uniquely arranged to create a picture. I do not know the full context of this artwork which presumably is depicting some strange interaction between a man and the Big Dipper constellation, but I believe that this energetic burst of creativity and passion by the calligrapher can still be universally appreciated.

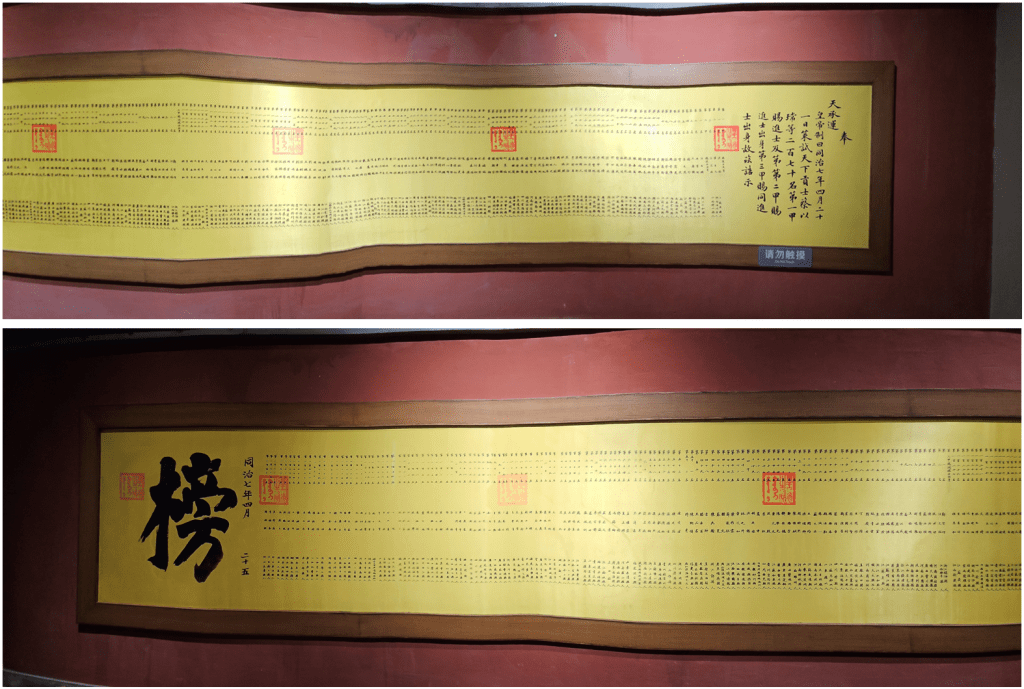

My favourite display in the Exhibition was the long golden scroll that announced the names of the scholars who had passed. It can only be imagined the depth of emotion aroused by this passive announcement board in the anxious scholars who must have read it back and forth, back and forth, searching for their names. The two hundred and seventy graduates whose names were published must have been elated, but who knows what sorrow and devastation was wreaked on the unknown number of scholars whose names did not make the final list.

It was interesting to see the diverse places from which the scholars originated. Some provinces were clearly highly represented, such as Jiangsu and Zhejiang located in the wealthy Yangtze Delta. But the scroll also included graduates from places far apart, such as the loess plains of the northern province of Shanxi and the often inaccessible karst regions of Guizhou in the southwest. On squinting, even the island of Taiwan received a mention on the honour roll. There is something awe-inspiring in the fact that the Imperial Examinations managed to seek out talent across the geographic vastness of Imperial China in a time preceding modern transportation.

The Biyong Hall

The central attraction of the Imperial Academy was the Biyong Hall, a name which reminisced on an academy for royal princes in the ancient Zhou Dynasty. The Hall was a square structure which rose serenely from the centre of a circular lake filled with red carp. There were four marble bridges by which one could cross over the water into the Hall. The Hall had an exquisitely designed ceiling with innumerable replicated dragon motifs and beneath this was a large golden throne where the Emperor supposedly sat and expounded on the Confucian classics to his scholars. While the majesty and solemnity of the place could not be denied, there was something rather perverse and insulting in the notion that China’s top literati who had studied all their lives should be lectured by an emperor who obtained his position via primogeniture rather than ability. Furthermore, there were incompetent emperors who likely knew less than the average scholar attempting to pass the provincial, nay the prefectural, examinations.

I also stumbled upon a curious scholar tree in the Academy with an impressive diagonally slanted trunk which required supports lest it be uprooted by its own weight. There was a string tied around it to designate it as an ancient, and hence culturally protected, tree. From a written description, I learned that the Qianlong Emperor thought this tree had an uncanny resemblance to a hunchback minister of his and therefore named it after him. I guess this could be considered a compliment?

This brought me to the end of my visit to the Imperial Academy. While there was a sense of grandeur in remembering this ancient institution, there were also mixed emotions on the legacy of these scholars. Ultimately, the Imperial Academy is a great choice to escape the crowds and learn about the fascinating examination culture of Imperial China, which is a less recognised and appreciated aspect of Chinese history. Hopefully one day I will get the chance to visit the Jiangnan Examination Hall in Nanjing to immerse myself further in this topic.

Isaac Tang is a Christian freelance poet who has recently published his first volume of poetry Glimpse of the Divine. Please click here for more details.

Leave a comment