By Isaac Tang

Even before I published my first volume of poetry Glimpse of the Divine, I wondered whether I would reach a substantial audience. For poetry, on a whole, appears to be declining as a literary form in the modern world. I believe that most people underappreciate it and find it fit for little use or purpose except, at most, as a diversional curiosity for children. Thus, my obsession with reading and composing poetry seems to be an unprofitable pursuit that is out of touch with the current generation.

The underappreciation of poetry is a tragedy because poetry has traditionally, for thousands of years, been enthroned at the apex of literature and, through painstaking experimentation and brilliant invention, has been a powerful tool to analyse and express the human experience. As Samuel Coleridge famously declared, poetry is superior to prose, as it is “the best words in the best order.” Those who have encountered great poetry would concur, for well-written poetry pleases both the ear and the eye, generates a strong emotional response and finds a way to remain lodged in one’s memory.

Contents

- Pleasing the Ear

- Pleasing the Eye

- Pleasing the Mind and the Heart

Pleasing the Ear

I say that well-written poetry pleases the ear first (before the eye), because poetry was there before the written language. In fact, some of the most famous poets, such as Homer and Milton, were blind. For most modern English speakers, the primary aural characteristic of poetry that jumps to mind is rhyme. However, for the ancients, it was rhythm that was paramount, rather than rhyme – Homer’s Odyssey was not rhymed but was composed in dactylic hexameter. For a large proportion of poetry up to the 20th century, poets abided by the concept of metre, whether this was made of iambs, trochees or dactyls. The use of a metre provides the poetry with a sense of order and, in epic poems like Paradise Lost, can heighten the sense of drama. Take, for example, the following excerpt from Henry Longfellow’s narrative poem Evangeline, where powerful descriptive words and imagery are inputted into dactylic hexameter to create a thrilling introduction to the unfolding tragedy:

“This is the forest primeval. The murmuring pines and the hemlocks,

Bearded with moss, and in garments green, indistinct in the twilight,

Stand like Druids of eld, with voices sad and prophetic,

Stand like harpers hoar, with beards that rest on their bosoms.

Loud from its rocky caverns, the deep-voiced neighbouring ocean

Speaks, and in accents disconsolate answers the wail of the forest.”

Excerpt from ‘Prelude’, Evangeline, by Longfellow (1847)

Contrary to what people may think, the metre does not constrain the poet. It is simply a tool in the poet’s workbox to fashion his, or her, creation. From personal experience, the metre is like a rudimentary pathway that the poet paves with marble words or colourful metaphors. It is like the hidden timber structure over which the poet builds a mansion. And when the poet suffers writer’s block, the metre remains like a guiding star and a grid full of possibility. Abiding by a metre does not mean that there cannot be any deviations. In fact, deviations from the metre can help to enhance and emphasise certain points or messages in the poem. I experimented with this myself, in my poem ‘Patience’, where the smooth, beloved iambic pentameter is rudely punctuated by an “incorrect” stress (bolded below), thus depicting the disordered state of mind:

“The railroads of my mind are troubling me:

The tracks are bent, tangled in sprawling mess . . .”

Excerpt from ‘Patience’

Humans delight from breaking rules. Indeed, some say that “rules are there to be broken”, and certainly some of the most astounding and innovative pieces of art arose from nonconformity to strict rules, like Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring or the glorious sprung rhythm of Gerard Manley-Hopkins. But without any rules, none can be broken, drastically reducing the sense of novelty. Therefore, the lack of metre in modern poetry is unfortunate and is probably a contributor to society’s general drift away from poetry. Those who abandon the metre, so prized by millennia of literati, lose the ancient magnetic appeal of poetry.

Because the works of poetry are usually shorter than the works of prose, the poet feels great pressure and obligation to pick only the most perfect words. They consider many aspects about a word before they set it on paper, including the number of syllables, the location of the stresses, the literal meaning, the hidden meanings and associations (i.e. connotations) and, importantly, the sound of the word. Alliterations and assonances are dearly loved and, particularly the former, add strong emphases that would be less acceptable in normal prose. Gerard Manley-Hopkin’s lavish use of alliteration allows for the speaker’s exhilaration at the sight of a soaring windhover to scintillate off the page:

“I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon . . .”

From ‘The Windhover’, by Gerard Manley-Hopkins (1877)

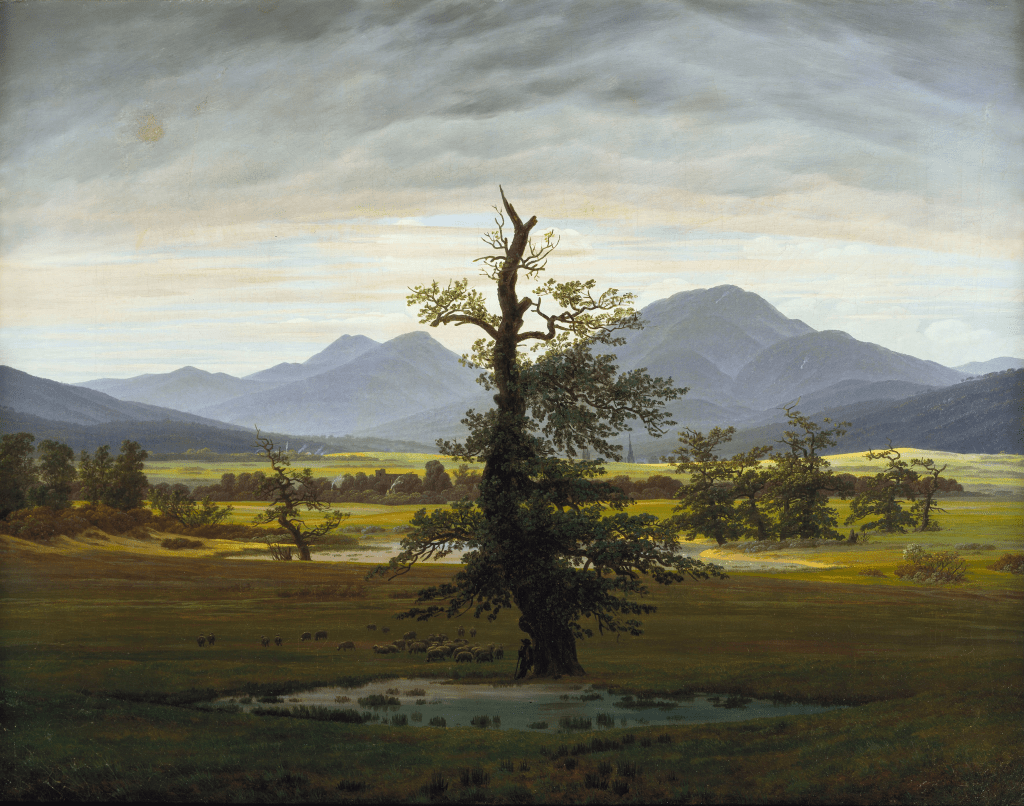

Another way in which words may be selected in poems is to satisfy the rhyming pattern. To many people, it is rhyme that sets poetry apart from prose. Rhyme, in the past, likely functioned as a mnemonic aid. It also significantly enhances the musical quality of the poem. There are fewer joys that compare to finding a poem where the poet manages to find breathtaking rhyme after rhyme that also fit perfectly into the overall structure and tale. Out of many brilliant examples, I here include a stanza from Tennyson’s ‘Lady of Shalott’ because of the quadruple and triple rhymes, which would have been no mean feat:

“But in her web she still delights

To weave the mirror’s magic sights,

For often thro’ the silent nights

A funeral, with plumes and lights

And music, came from Camelot:

Or when the moon was overhead

Came two young lovers lately wed;

‘I am half sick of shadows,’ said

The Lady of Shalott.”

From ‘The Lady of Shalott’, by Alfred Lord Tennyson (1842)

Pleasing the Eye

For some ingenious poets like George Herbert, the visual appeal of rhyme schemes is explored in innovative ways. His poem ‘Paradise’ is a ‘pruning poem’, where each successive rhyme is shorter by one letter, symbolising the pruning of the soul by God to perfection:

“When thou dost greater judgments SPARE,

And with thy knife but prune and PARE,

Ev’n fruitful trees more fruitful ARE.”

From ‘Paradise’, by George Herbert (1633)

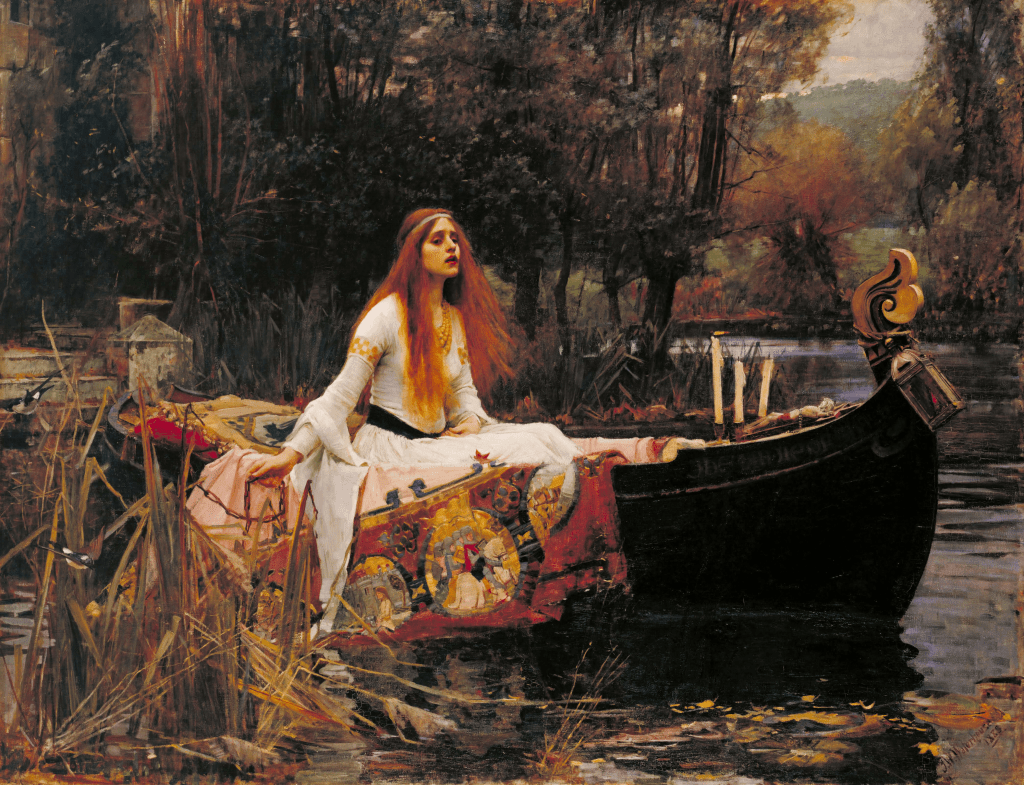

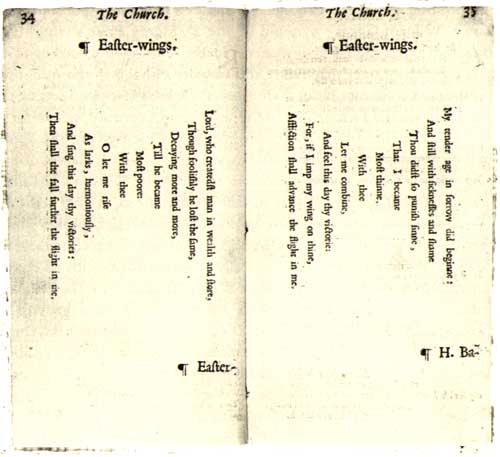

George Herbert is also famous for his picture poems, which show the power of poetry to liberate words from conventional structures, rearranging them in unexpected ways. In ‘The Altar’, the length of each line is modified such that the entire poem becomes a pictorial representation of a classical altar. In ‘Easter Wings’, the words are arranged and rotated so that two sets of wings appear to emerge from the page. In these poems, Herbert still follows the regulations of rhyme and metre, which offers both sensory and intellectual delight for the reader. Lewis Carroll, the mathematician and writer, also springs to mind, who displayed much literary brilliance in his rhymes and acrostic poems, particularly his double acrostic poem to a child-friend, Gertrude Chataway.

Another visual aspect of poetry is the use of space. Most poems take up perhaps 50% or less of the page they are written or printed in. They reflect two very important principles, that “less is more” and that “brevity is the soul of wit” – the latter gem of wisdom provided ironically by the very verbose Polonius in Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In my opinion, the best examples of extreme succinctness are from Chinese poetry, where complex ideas are condensed into a few characters, and Japanese haikus (comprising of 3 lines and a total of 17 syllables each) which compel the reader into a state of quiet reflection. Indeed, the greatest function of poetry is its ability to slow the frantic pace of life and enable a person to contemplate a single concept, or even a single word, in a deeper and more meaningful way, and this is something that the modern world would benefit from.

Pleasing the Mind and the Heart

At this point, I notice that I have written far more than I intended. It is probably outside the scope of a modest online article to touch on the many different complex ideas and philosophies that poets have managed to integrate into their work, while maintaining form, visual aesthetics and a harmonious sound. Poets as different as John Milton (famous for his dramatic blank verse) and Emily Dickinson (famous for her untitled, hymn-like poems punctuated with numerous dashes) demonstrate the versatility of poetry as a vehicle for human expression, which far surpasses the effects attained through prose alone. It is no wonder, then, that Emily Dickinson, alone in her Amherst room, boasted that she “dwell[ed] in Possibility”, a blissful realm “fairer” than prose. That is why, even though the sun threatens to set on poetry in the 21st century, I believe that the composition of poetry will continue to play a large role in my own life.

“I dwell in Possibility –

A fairer House than Prose –

More numerous of Windows –

Superior – for Doors –

Of Chambers as the Cedars –

Impregnable of eye –

And for an everlasting Roof

The Gambrels of the Sky –

Of Visitors – the fairest –

For Occupation – This –

The spreading wide my narrow Hands

To gather Paradise – ”

466, by Emily Dickinson

Leave a comment