By: Isaac Tang

Wu Lien-Teh is a name that perhaps sounds more familiar now, after the COVID-19 pandemic swept through the globe and triggered mass lockdowns, mask wearing and “social distancing” rules. Dr Wu is credited with spectacularly suppressing the Manchurian plague in Northeastern China at the beginning of the 20th century (1910-11) with various tactics, including aggressive quarantines, health system reform and (supposedly) inventing the predecessor to the N95 mask. As a doctor working in Australia, but born in Malaysia with Chinese heritage, I naturally took a great interest in learning more about this curious historical figure.

With help, I hunted down a copy of his autobiography Plague Fighter: The autobiography of a modern Chinese Physician, which was found in some dusty, forgotten university shelf. In spite of its occasionally pompous tone, it is a remarkable account, not just of the medical and scientific progress of the time (which admittedly can be quite tedious in some sections), but also the complex clash of cultures and philosophies that characterises East Asian history of the early 20th century. The fact that Dr Wu was a 1) Malaysian-born Chinese doctor with 2) a name that could be spelt at least three different ways 3) who studied in England (and shortly in Germany and France), 4) married the daughter of a Fuzhou Christian missionary and 5) worked in Manchuria to delay the collapse of the feeble Qing dynasty against the encroachment of the West, Russia and Japan illustrates how fascinating (and frightening) these cross-cultural encounters can be. His brushes with multiple powerful figures, including Churchill, Sun Yat-sen and Yuan Shikai, and his presence at certain historically momentous events are a thrilling read, and render him somewhat like an Asian Forrest Gump.

CONTENTS

- Childhood in Malaya

- Education in Europe and Effect of European Colonisation

- The Decline of the Late Qing Dynasty

- The Manchurian Plague and its Challenges

During his youth in Malaysia, he was the model immigrant child. His father had a rag-to-riches story, coming from China’s Guangdong province to the island of Penang on the northwestern corner of the Malayan peninsula with only a set of clothes, a straw mat and a pillow to call his, before making a career for himself as a prosperous goldsmith. I have not been to Penang for many years, but Wu Lien-Teh paints an idyllic picture of it, describing the “enchanting beaches”, “gorgeous mountains” and the assorted fruit trees on Penang Hill. He was an exemplar student, full of academic promise and ambitious competitiveness, ultimately winning the prestigious Queen’s Scholarship. This Scholarship was a British initiative to fund for two boys every year from the Straits Settlements (Penang, Malacca, Singapore) to complete tertiary studies in Great Britain. Travelling from South-East Asia to North-Western Europe was certainly no easy task, physically and emotionally. He wrote about the heartache and the conflicting feelings he developed on his voyage to Britain before deciding to cut off his queue. Despite being a well-known symbol of a Chinaman at the time, the queue was a Manchu hairstyle that the Qing dynasty imposed on the majority Han population as a mark of loyalty. He was embarrassed by the unwanted attention his queue attracted, but then felt grief after he cut it off, believing that he had discarded a part of his identity.

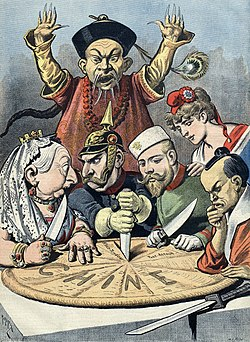

Interestingly, he was quite adamant that he did not suffer much racism during his time in England and other parts of Europe, except during the aftermath of the Boxer Uprising, which was a violent, imperially-sanctioned uprising against colonialists and missionaries in China at the turn of the century. He stated being threatened with stones on the streets of London by random passersby. It is perhaps a little hard to believe that this was the only period of time where he suffered due to his race, especially given the hysteria over ‘Yellow Peril’ that swept across Europe and the United States during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, where people feared that the Asian population would one day overpower and subjugate the Western world who had colonised and enslaved them. However, as he repeatedly emphasised, it was likely true that he also met many Europeans who were open-minded, kind and generous.

It appears that he suffered much more discrimination in his homeland where colonialist mindsets built on the concept of racial superiority were the foundation of governance. He was barred from joining the Colonial Medical Service in Malaya as the job was reserved only for Europeans. He got into further trouble when he became outspoken in his anti-opium activities, leading to an undignifying search of his Ipoh clinic where the discovery of an ounce of opium became the pretext for a criminal investigation. Disillusioned by these events, when he received an invitation from Yuan Shikai to be the vice-director of the Imperial Medical College at Tianjin (Northeastern China), the prospect had much appeal. From his writings, it seems that Dr Wu was also spurred on by a desire to help China, his ancestral land, to strengthen itself in a rapidly modernising world.

This help would have been much needed as China was then still in its ‘Century of Humiliation’, weakened by foreign powers. Examples of this humiliation are countless, including the Opium Wars and the senseless looting and destruction of the Old Summer Palace by British and French forces. However, other examples are smaller but no less significant, such as an infamous sign hung at the entrance of Huangpu Park (known then as ‘The Public Garden’) in Shanghai. This sign contained a few painted stipulations, that “no dogs are permitted into the garden” and straight afterwards that “no Chinamen are admitted inside this garden.” Whilst many, in various sites, have claimed that this sign was fabricated and only part of a Bruce Lee movie, clearly this sign was indeed present when Dr Wu arrived in Shanghai in 1908 and it stirred so much fury and ire that he dedicated three paragraphs to memorialise this indignity.

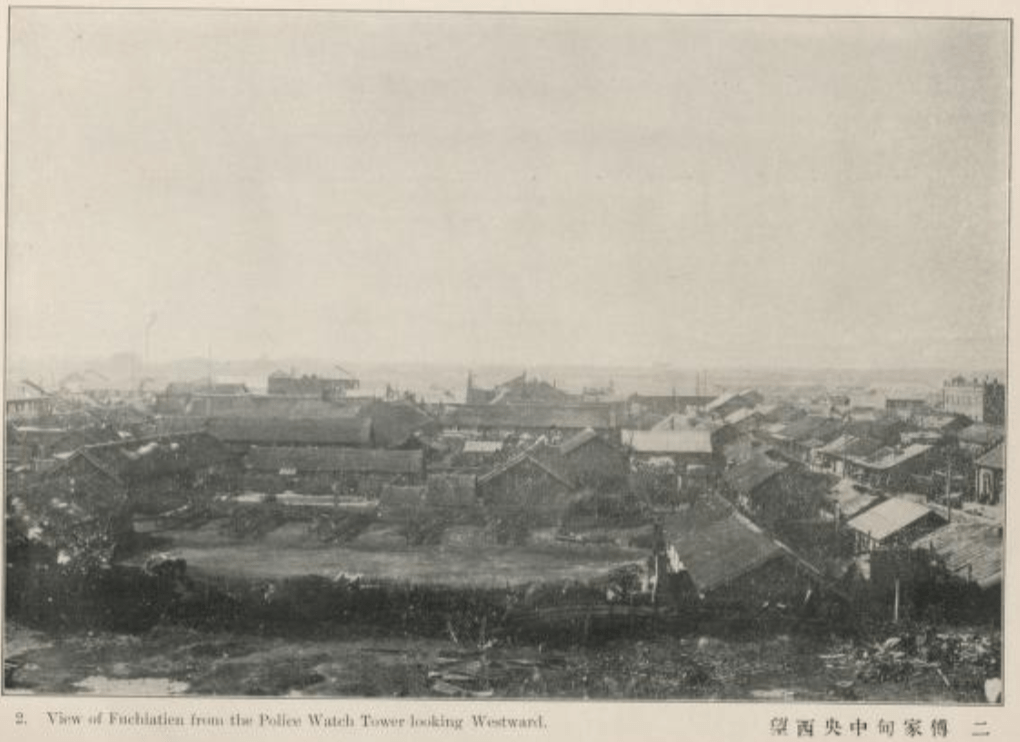

When Dr Wu reached North China, there were numerous signs of China’s ongoing decline. The contrast between the Russian/Western and the Chinese living quarters was particularly stark in Harbin, where he investigated reports of a plague outbreak. He praised the geometric and thoughtfully designed streets of Pristan, the Russian quarter of Harbin, but quailed at the sight of the crowded and dilapidated Fuchiatien, the Chinese quarter. He found the disinterested conduct and overall incompetence of the local magistrate disappointing, evident even from the dirty gown he wore and his appearance which suggested opium addiction. In one of his travelogues ‘A Visit to Si’an, China’s Most Ancient Capital’ (1933), he lamented that the city “had little to show of the glorious past” when it was the illustrious capital of the opulent Tang dynasty. China, in the early 20th century, appeared to be a far cry from the power it yielded as the ‘Middle Kingdom’ for millennia.

However, back in Harbin, the plague outbreak with its exponential death toll was a medical crisis that threatened to become a political one. Russia and Japan were keenly following the progress of the plague as it spread via the railway lines, with the latter even beginning plans for a secret invasion by stationing troops at the Korean border. From his rapid assessment of the epidemiology of the plague, Dr Wu concluded that the transmission was purely pulmonary and therefore, suppressing this would require radical preventative measures, including strict quarantine laws, mask-wearing and mass vaccination of the population. Another idea he proposed, which the Qing government duly accepted, was the mass cremation of plague victims with kerosene, likely scandalising the community. This action would have appeared to go against the central virtues of filial piety and ancestor veneration.

In light of these unconventional proposals, it is likely that the Chinese community murmured against Dr Wu. It must be remembered that he was part of the overseas Chinese diaspora rather than native-born. His English education would have increased suspicions in some, and his unfamiliarity with the Chinese language was a source of embarrassment for him. During his expedition to Harbin, he needed a the help of a faithful medical student assistant (Lin Chia-Swee) to help translate for him. His lack of the queue and his Western clothing furthermore would have consolidated his “outsider” status.

Sadly, he also was an “outsider” to the Westerners, despite his Western training. He was particularly despised by a French doctor Dr Mesny, who felt that the crisis had to be handled by a European instead of a mere “Chinaman.” Being only thirty years old, Dr Wu’s age was also a sore point to Dr Mesny, who was incredulous that a “novice” like him could have been appointed to this position, fuelling a tirade of derogatory remarks. Dr Mesny refused to believe that the plague was transmitted by the air, continuing to stick by his belief that rats were the root cause of it. Dr Wu was shaken and furious with Dr Mesny’s outburst, but was later vindicated when the latter neglected to wear protective masks while examining plague victims. Dr Mesny contracted the plague and died in a matter of days, a tragedy which became the turning point for many in Harbin who began to accept the advice of Dr Wu.

After his work in the Manchurian plague, he continued in other public health initiative in post-imperial China before returning to Malaya where he set up a clinic in Ipoh, a town affectionately known as the ‘Mountain City’ for its cradled position amongst rainy, viridian mountains. Having lived in Ipoh for part of my childhood, I was surprised that I had never heard of Wu Lien-Teh then. This brief discourse on his autobiography certainly does not give full credit to the scope of his achievements, but hopefully it has shown what a unique and interesting role he played in a tumultuous and complex time in history.

Leave a comment