By: Isaac Tang

There was a time when I was thirteen or fourteen when I thought I had lost interest in reading. The typical books teenagers were supposed to like were either dystopian science fiction or romances, neither of which were to my taste. Thankfully, the end of this drought came with the discovery of the richness and vibrancy of Christian poetry.

- Hymns

- John Bunyan

- John Milton

- John Donne

- George Herbert

- Christina Rossetti

- Gerard Manley-Hopkins

- Present Day Influence

It started with looking at the hymns in old hymnals and songbooks. What I love about traditional hymns are their neat, regular appearance. Well-proportioned lines, firmly guided by metre and consistent rhymes provide a sense of peace, calm and orderliness that contrast with what appears to be the chaotic and lawless modern world. I feel that this feature of traditional hymns reminds us of the constancy of God and his never-changing nature despite what humans do. When I was little, another aspect that I loved about hymns was their dogmatic nature, unambiguously reiterating the tenets of the Christian faith. Therefore, I was shocked when I read C.S. Lewis unflattering description of hymns as “fifth-rate poems set to sixth-rate music.” Hymns, however, were the start of my journey as a Christian poet.

My goal in life at that age, which I hope remains the same, was to bring praise to God. Thus, I sought for examples of braver and more vivid expressions of the Christian experience which I could emulate. I think that all who dive into Christian poetry will eventually encounter a few particular poets, which are most of the poets whom I will discuss here. However, John Bunyan, best known for his allegory The Pilgrim’s Progress and the little songs included within (e.g. ‘Who Would True Valour See), is not universally acclaimed as poet. However, John Bunyan’s poems appealed to me because of his use of extremely extended, and frankly outlandish, metaphors. For example, in ‘Meditations Upon A Candle’, every aspect of a candle is dissected and compared in meticulous detail to a Christian man, unrelentingly extracting every component possible for spiritual edification. ‘Meditations Upon An Egg’ is another example. To my younger self unfamiliar with much literature, these poems provided immense delight.

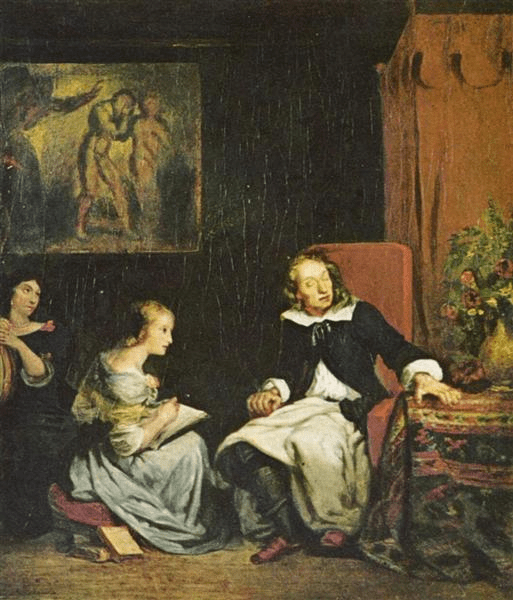

John Milton, on the other hand, was recommended by many. John Wesley praised his work, C.S. Lewis wrote highly of him and I sometimes imagine the Romantic poets sitting in their cottages, huddled around a warm fireplace during a dark night reciting the long, long passages of supernatural warfare. I had some hesitation before reading Paradise Lost, chiefly due to concerns that Milton had entertained heretical views, especially regarding the Trinity. However, when I began, I was quickly swept up by the grandeur of this magnum opus, from the mighty first sentence, to the Archenemy’s journey to the newly created world, to the intensely bittersweet ending, when our first Parents “hand in hand…took their solitary way.” To be honest, unlike the plays of Shakespeare, other than the first and last sentences, there are not many lines that have stuck in my memory. Instead, the vivid imagery and narrative arch are what remain, impressing on me an unmistakable realisation of the power within language and imagination to create a glorious and complex realm of its own. This, I learnt, is poetry at its mightiest.

However, as awe-inspiring as lengthy narrative poems can be, I still gravitate towards smaller and more compact pieces. In my opinion, one exquisitely coloured ukiyo-e print can stir the same emotions as the Sistine chapel ceiling. Therefore, my discovery of the metaphysical poets was truly life-changing. When I say metaphysical poets, I really only mean two – John Donne and George Herbert. The others, including Henry Vaughan, have not affected me much. The former, famous for his unexpected poetic conceits, has an incredibly daring style. Before reading his poems, I never conceived the notion of comparing a human to a map, or doctors to cartographers, as he does in his poem ‘Hymn to God, my God, in my Sickness.’ His cycle of sonnets ‘La Corona’, is innovative in its construction and contained many brilliant observations, especially in ‘Anunciation’, where the Angel relates the mysteries of the Incarnation, that Mary will become “[her] maker’s maker, and [her] Father’s mother.” His use of puns is also amusing, like in his poem ‘A Hymn to God the Father,’ where he plays on the phonetic similarity between his surname and the word “done”. Sadly, my full enjoyment of his work is hampered by his (earlier) secular poems that are often licentious and misogynistic in content although his literary skills and ingenuity are quite unparalleled.

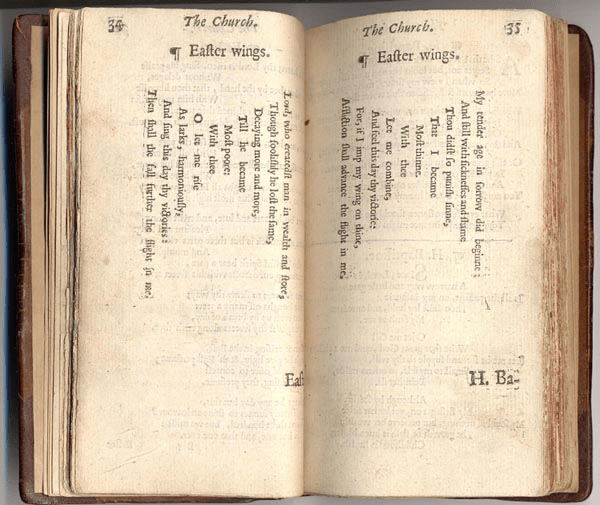

Donne’s less famous counterpart in the world of metaphysical poetry is George Herbert. He may be less known in the modern world but he is without doubt my favourite poet. When I imagine Herbert, I see a slender, meek and a little sickly man ever dressed in his neat priestly robe residing in a humble cottage as a countryside parson. But his writings are vibrant and fierce, and he tackles a wide range of subjects, converting and synthesising a large portion of the Christian experience into colourful verses. Nothing is too small to be excluded; even the simple act of “sweep[ing] a room”, if done with the aim to praise God, becomes an “Elixir”, indeed the “famous stone that turneth all to gold.” He contemplates the light streaming through stained glass and compares it to a preacher, he meditates on the design of the church floor and the lessons it imparts, and he adores the small flowers even as they wilt, finding spiritual meanings in everything he encounters. Other times, he can be angry and hot-headed, like the time he “raved and grew more fierce and wild at every word” in ‘The Collar’ and the time he lamented Job-like and threatened to “seek some other Master out” in ‘Affliction (I)’. The latter is an extremely bold statement, as Christians know that there are only two masters. But this demonstrates the difference between devotional poems and the simple congregational hymns. The poet does not shy away from using provocative words and phrases, because illustrating the truth of the experience, not dogma, is his aim. It shines a rare light into the beauty and complexity of human brokenness. Regarding his literary techniques, Herbert has a large arsenal of innovations and creative tools which would take many pages to go through, ranging from rhyme schemes to line length to multilingual puns. However, needless to say, it was a blessing that when he gave the manuscript of his collection of poems The Temple to his friend Nicholas Ferrar, the latter decided to publish it (rather than burning it, as Herbert suggested) for the advantage of future generations.

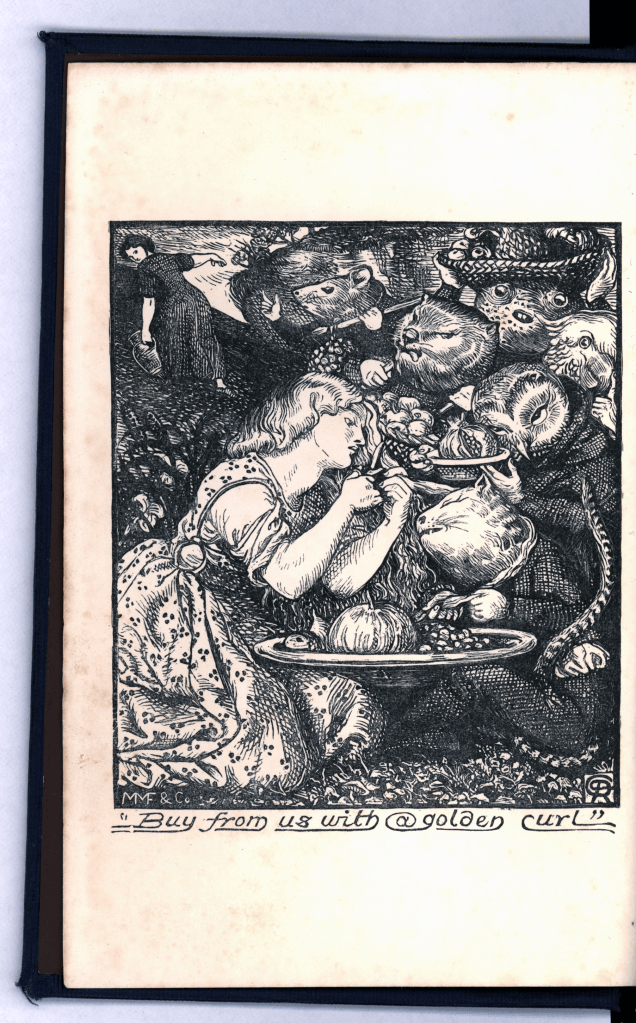

For some reason, the modern poets that catch my attention are those leaning towards the Roman Catholic side of the spectrum of Christianity. Perhaps it is because they seem to appreciate the mysteries of God and the beauty of sacraments in a rapidly transforming world. The first poet is Christina Rossetti, whose brother founded the Pre-Raphaelite movement. She professed herself an Anglican for her whole life but showed sympathy for the Oxford Movement. Her works have a wide range of emotions, from serious pensive sonnets, to heartbreaking elegies (‘At Home’, ‘L.E.L’), to childlike narratives (‘Goblin Market’), to songs of ebullient joy (‘A Birthday’). The themes of her poetry that resonate most with me are the theme of worldly deception (‘The World’) and the theme of the insufferable self – as she groans in ‘Who Shall Deliver Me?’, “God strengthen me to bear myself; \that heaviest weight of all to bear, \inalienable weight of care.” It has been suspected by several literary critics that Rossetti may have had bipolar depression; however, though she recognises “[her] life is in the falling leaf”, she still manages to whisper, “O Jesus, rise in me!” (‘A Better Resurrection’)

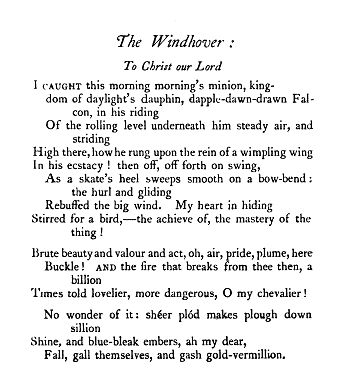

One poet who definitely had depression was Gerard Manley-Hopkins, as he cries out in his so-called ‘Terrible Sonnets’, “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall \Frightful”. The wonderfully constructed rhythm and the carefully positioned words marvellously conjure an image of slippering steepness and pitch darkness below. As a Jesuit priest who lived far from home, lonely and isolated in a professor job that he did not enjoy, he took the struggles with hardship and religious doubt and expressed them in his art. But his work was not all doom and gloom; there are numerous moments of awe and worship, including ‘God’s Grandeur’, ‘Pied Beauty’ and ‘The Windhover’, which are without doubt some of my favourite poems. He also developed and invented poetic techniques that exude an incomparable vibrance and energy, all of which can be seen in the last 2 lines of ‘The Windhover’: “blue-bleak embers, ah my dear, fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermillion.” Firstly, it is the astute observation that shows the majestic metamorphosis of something as “bleak” as an ember (which alludes to the destruction of something by fire) into “gold”. Next, it is the ceaseless use of alliteration and assonance that contributes to the emotional crescendo. Lastly but not least is his use of sprung rhythm (his invention) which provides flexibility for the poet but still, unlike modern free verse, has a tight structure to it as each line has (usually) five feet. It provides a strong sense of movement without the threat of descending into monotonous predictability.

For me, the impact these poets have had on me is profound, conscious and unconscious. The ways I think about theological topics and express my understanding of these concepts display the footsteps of these literary masters. I am thinking of Donne when, in my poem ‘The Magnet’, I compare the soul to a piece of metal struggling against the magnetic influence of the world, or when I say “every human is a planet” in ‘The Human Paradox’. The latter poem is also composed with dramatic blank verse in the style of Milton, echoing Paradise Lost in its lament for humankind. I absorb Herbert’s love of deriving divine messages from simple events in my poem ‘One Winter Evening’, as the viewing of a sunset becomes a contemplation on God’s gift of appreciating beauty around us. I adopt Herbert’s fondness for puns, particularly in ‘Trisagion’, where the homonyms “holy”, “holey” and “wholly” become a medium to discuss the glory of the Trinity. Hopkins’ sprung rhythm also makes several appearances, especially when I use it to describe the choppiness of my speech accent (in ‘The Accent’) and the capricious nature of humankind (in ‘People’). However, most of my poems ultimately have simple structures and four-line stanzas, reflecting the long-lasting influence that traditional, pious hymns will continue to have for me.

Isaac Tang is a Christian freelance poet who has recently published his first volume of poetry Glimpse of the Divine. Please click here for more details.

Leave a comment